Just the other day we received a comment on one of our photos in the new Flickr Commons set of lantern slides from the Archives of American Gardens. A visitor was interested to know whether or not the black border on one of the lantern slides within the set was original. (For the record, the border is in fact original to the slide.) Looking into this inquiry, I received an education in how lantern slides are made, and so I thought I would share. “Magic Lantern Slide” technology actually predates the invention of photography. Originally, glass slides made from drawings or paintings were held up in a device, lit up by lantern or candle light, and projected on a wall. The resulting projections were often animated and accompanied by music as a form of entertainment. Understandably, these fantastical lantern slide shows fascinated audiences living in a time before film and photography.

Just the other day we received a comment on one of our photos in the new Flickr Commons set of lantern slides from the Archives of American Gardens. A visitor was interested to know whether or not the black border on one of the lantern slides within the set was original. (For the record, the border is in fact original to the slide.) Looking into this inquiry, I received an education in how lantern slides are made, and so I thought I would share. “Magic Lantern Slide” technology actually predates the invention of photography. Originally, glass slides made from drawings or paintings were held up in a device, lit up by lantern or candle light, and projected on a wall. The resulting projections were often animated and accompanied by music as a form of entertainment. Understandably, these fantastical lantern slide shows fascinated audiences living in a time before film and photography.

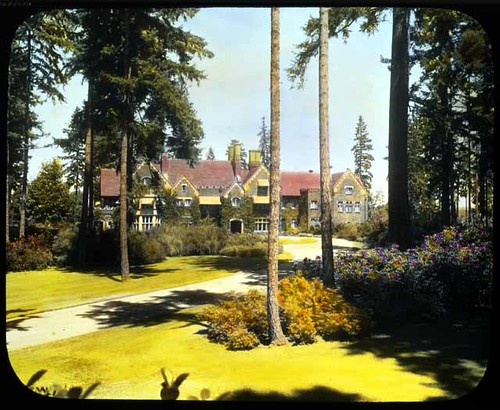

[A 19th century glass magic lantern slide of a tiger. The eyes and mouth are both painted on separate, movable plates, creating the illusion of an animated tiger when the slide is projected. From YouTube user, iamthedigitalme.] When photography emerged in the mid-1800s, it was a natural fit for the “Magic Lantern” technology. Basically, a photographic lantern slide is a positive print of a photograph on a glass slide. Often times the photographic negatives were painstakingly hand-colored to make them even more visually enticing. Many photographic lantern slides were also “matted” by a piece of opaque paper laid on the slide, which both masked out edges or parts of the image not wanted in the frame, and created the desirable aesthetic appearance of a mounted photograph. Finally, a second slide of glass was laid atop the glass slide with the positive print and these two pieces of glass were bound firmly together by pasting a strip of paper around the edges. The sandwiched glass plates held the matte or mask in place and also protected the positive photographic print from dust, scratches, and the like. The final slide was then ready to be viewed in a lantern slide projector. Photographic lantern slides took off in the late 19th century as a popular form of entertainment, and in addition to educators, missionaries and salespeople soon began to use Magic Lantern slides to visually entice the audience while educating, spreading their messages, and peddling their wares. In this sense, lantern slides were a kind of precursor to the Power Point presentations we’re all so familiar with now.

By the 1930s and 40s, lantern slides dropped off in use as overhead projectors and slide projectors took their place. However, for me, lantern slides continue to hold a certain charm. I imagine the speechless awe of an audience as an image rises up the wall and shimmers there. And I imagine a photographer, hunched over a slide with a tiny paintbrush, coloring his world beautiful, and capturing some of that magical essence between these thin sheets of glass.

By the 1930s and 40s, lantern slides dropped off in use as overhead projectors and slide projectors took their place. However, for me, lantern slides continue to hold a certain charm. I imagine the speechless awe of an audience as an image rises up the wall and shimmers there. And I imagine a photographer, hunched over a slide with a tiny paintbrush, coloring his world beautiful, and capturing some of that magical essence between these thin sheets of glass.

Produced by the Smithsonian Institution Archives. For copyright questions, please see the Terms of Use.

Leave a Comment