We all know that the Smithsonian is a great destination for families, but, did you know that a family actually lived in the Castle and that kids went on expedition and worked in the field with their scientist dad?

The first Secretary of the Smithsonian, Joseph Henry (1846-1878)—along with his wife, Harriet, and their three daughters, Caroline, Helen, and Mary—lived in specially designed apartments in the Castle from the year opened (1855) until Henry’s death in 1878. Although it seems a grand address, the Castle was apparently very drafty and cold in the winter and not quite the fairy tale environment the architecture suggests.

The Henrys were not the only inhabitants to prowl the Castle halls. Spencer Baird, the Assistant Secretary and later second Secretary (1878-1887) of the Smithsonian, invited a group of bachelor scientists to live in the Castle between expeditions to work on their specimens and reports. This boisterous group—Henry Ulke, William Stimpson, Robert Kennicott, and Henry Bryant—dubbed themselves the Megatherium Club, after a giant extinct sloth. And, it is reported, they held sack races in the Great Hall and serenaded Henry’s daughters. There are no reports as to how Secretary Henry felt about these antics, but scholars speculate he was not happy about it.

Although it is cold in the winter, August in Washington, DC is hotter than the hinges of H*!! and, before the days of AC, anyone who could fled the heat and humidity of the city for cooler climes. Traditionally, Secretaries of the Smithsonian were scientists and in August they would shed their administrative duties and go into the field to continue their research, often times with spouses and families in tow.

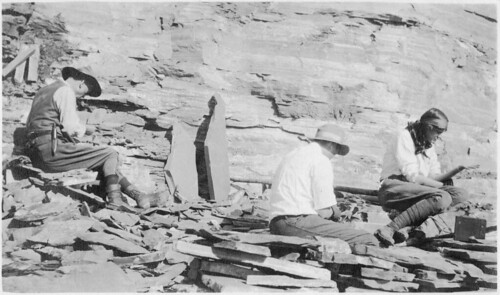

Secretary Charles Walcott (1907-1927) was a geologist and he, his wife, and younger children, Helen, Sidney, and Benjamin ventured into the Canadian Rockies every August to survey, photograph, collect fossils, and to fish and swim, too. They’d pack in to their alpine camp on horseback and “roughed it” (with linens on the lunch table) for the month . . . Some Smithsonian employees and their families didn’t leave the city to consort with nature.

William Mann, for example, the Director of the National Zoo (1925-1956), and his wife Lucy, on occasion, brought tiger cubs, birds, and other babies who needed tending in their Northwest Washington home.

To me, stories like these make the Smithsonian seem less “institutional” and more like the exotic, eccentric arm of your family you always have fun with.

Produced by the Smithsonian Institution Archives. For copyright questions, please see the Terms of Use.

Leave a Comment