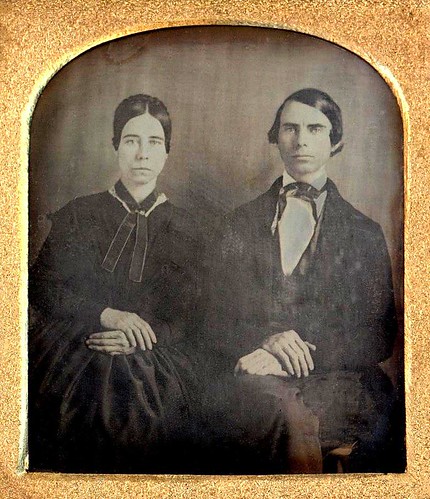

When I read Laurie Lambrecht’s recent contribution to click! about wedding photography it triggered more thoughts about the comparisons between photography’s future and its past. While many fine art photographers known for other work pay the bills with work at weddings, by capitol “H” history of photography standards, wedding photography is usually seen as the last refuge of scoundrels, the photographic equivalent of Adam Sandler in The Wedding Singer. I heard of one photographer who only shoots people’s shoes at a wedding. But photographs of brides and bridal parties, brides and grooms, and relatives have been with photography from the beginning.

When I read Laurie Lambrecht’s recent contribution to click! about wedding photography it triggered more thoughts about the comparisons between photography’s future and its past. While many fine art photographers known for other work pay the bills with work at weddings, by capitol “H” history of photography standards, wedding photography is usually seen as the last refuge of scoundrels, the photographic equivalent of Adam Sandler in The Wedding Singer. I heard of one photographer who only shoots people’s shoes at a wedding. But photographs of brides and bridal parties, brides and grooms, and relatives have been with photography from the beginning.

At the moment photography entered the United States and our visual vocabulary it brought with it a mix of conflicting emotions. It was on the one hand a miraculous invention that could “let nature paint herself” exactly. As photography studios proliferated portrait photographs had more and more currency in the world and a walk down most American main streets would be a walk down a gallery of faces that glinted out from studio storefronts. To read any of the many accounts of such an experience the act of seeing could also be a bit spooky. And it was speculated that revealing your face to the camera for a portrait might also produce a portrait of the “inner you,” and that could be embarrassing, even dangerous. Long before the police blotters filled up with mug shots and an entire theory of visual forensics was created, writers speculated that criminals could be revealed by the camera eye. The medium also offered to a mid-nineteenth century America struggling with the chaos of an economic crisis (a national malaise not to be solved financially or spiritually until the 1849 discovery of gold in California) material for an engaging and uplifting story about the good and evil effects of looking, seeing, and posing. Popular fiction, especially in the new form of the sentimental short story, increasingly included allusions to photography. In many stories a hero, usually a young professional man adrift in the big city, sees a cased daguerreotype in a studio’s storefront display, falls in love with the image, and becomes obsessed with meeting its “original.” After several exciting adventures fending off brigands and thieves he finds his true love, and in a daguerreian love-at-first-sight happy ending, marries the girl. The true and noble character of both hero and nation are perpetuated, all thanks to the photograph.

At the moment photography entered the United States and our visual vocabulary it brought with it a mix of conflicting emotions. It was on the one hand a miraculous invention that could “let nature paint herself” exactly. As photography studios proliferated portrait photographs had more and more currency in the world and a walk down most American main streets would be a walk down a gallery of faces that glinted out from studio storefronts. To read any of the many accounts of such an experience the act of seeing could also be a bit spooky. And it was speculated that revealing your face to the camera for a portrait might also produce a portrait of the “inner you,” and that could be embarrassing, even dangerous. Long before the police blotters filled up with mug shots and an entire theory of visual forensics was created, writers speculated that criminals could be revealed by the camera eye. The medium also offered to a mid-nineteenth century America struggling with the chaos of an economic crisis (a national malaise not to be solved financially or spiritually until the 1849 discovery of gold in California) material for an engaging and uplifting story about the good and evil effects of looking, seeing, and posing. Popular fiction, especially in the new form of the sentimental short story, increasingly included allusions to photography. In many stories a hero, usually a young professional man adrift in the big city, sees a cased daguerreotype in a studio’s storefront display, falls in love with the image, and becomes obsessed with meeting its “original.” After several exciting adventures fending off brigands and thieves he finds his true love, and in a daguerreian love-at-first-sight happy ending, marries the girl. The true and noble character of both hero and nation are perpetuated, all thanks to the photograph.  Wedding portraits continue to tell a good story and photographs, including some by Laurie Lambrecht, add an important piece to the cultural narrative. Each week the New York Times' Sunday Styles includes a substantial section of wedding photographs. Formal portraits of couples and individual brides wearing white are more often than not surrounded by informal poses of couples at home or outdoors. Following the rules of the pose—couples are urged by the Times editor to keep their eyebrows on the same level—they seem to all be part of a balanced formula of happiness. On the newspaper page a new age of wedding diversity—black, white, gay, and straight—forms a comforting pattern of photographic sameness. Along with the picture is a text that details the courtship. Though individual details may differ, in addition to the usual wedding information of age, occupation, and lineage, the text that accompanies each photograph includes a bit of drama, sometimes tragedy, but always resolution. In the end, someone always gets married.

Wedding portraits continue to tell a good story and photographs, including some by Laurie Lambrecht, add an important piece to the cultural narrative. Each week the New York Times' Sunday Styles includes a substantial section of wedding photographs. Formal portraits of couples and individual brides wearing white are more often than not surrounded by informal poses of couples at home or outdoors. Following the rules of the pose—couples are urged by the Times editor to keep their eyebrows on the same level—they seem to all be part of a balanced formula of happiness. On the newspaper page a new age of wedding diversity—black, white, gay, and straight—forms a comforting pattern of photographic sameness. Along with the picture is a text that details the courtship. Though individual details may differ, in addition to the usual wedding information of age, occupation, and lineage, the text that accompanies each photograph includes a bit of drama, sometimes tragedy, but always resolution. In the end, someone always gets married.

Merry Foresta is the Former Director of the Smithsonian Photography Initiative.

Produced by the Smithsonian Institution Archives. For copyright questions, please see the Terms of Use.

Leave a Comment