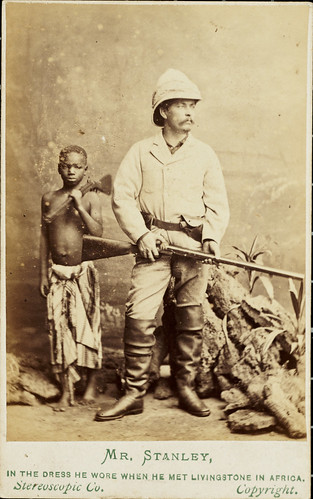

The above photo of Henry Morgan Stanley and a young boy named Kalulu has provoked more discussion and debate than any other photograph we have on the Smithsonian Commons, and reading through the comments made me want to know who Kalulu might have been.

Long story short, Stanley was a journalist hired by the New York Herald to track down Dr. David Livingstone—a missionary who hadn’t been heard of since his 1866 departure for Africa to search for the source of the Nile. Stanley was, in fact, successful at finding the doctor in 1871 and greeted him with possibly the most famous words in colonial history: “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?”

As our carte de visite suggests (and as the Smithsonian Institution Libraries noted on Flickr) Kalulu was Stanley’s gun bearer, servant, page, and “sometimes adopted child.” Kalulu was a young slave given to Stanley by an Arab merchant while on his way to find Livingstone. Because Stanley didn’t like the boy’s name (Ndugu M’hali, meaning “my brother’s wealth”), he christened him “Kalulu,” the Swahili term for a young antelope. Kalulu quickly captured Stanley’s attention and trust as Stanley noted: “Kalulu, a boy of seven . . . understands my ways and mode of life exactly. Some weeks ago he ousted . . . the chief butler by sheer diligence and smartness.”

Shortly after discovering Livingstone, Stanley went to England for a lecture circuit and arranged to have studio portraits taken with Kalulu at the London Stereoscopic & Photographic Company. The portraits are incredibly stiff: ours shows a shy and uncomfortable-looking Kalulu holding a gun behind a serious Stanley. Another in the series shows Kalulu serving tea to a severe-looking Stanley who has a riding crop conspicuously propped on his knee. As a sign of the times, neither of these two photos even acknowledges Kalulu in the captions. However, a third pictures Kalulu alone, in dungarees, boots, and with his khanga (sarong) wrapped around his shoulders and an incongruous fan in his hands. The first two photos clearly situate Kalulu in a subservient role—behind Stanley and with his eyes cast downward and aside. And yet the third photo (even with its offensive caption that implies Kalulu is somehow owned by Stanley), mentions Kalulu by name and presents a self-possessed boy.

Shortly after discovering Livingstone, Stanley went to England for a lecture circuit and arranged to have studio portraits taken with Kalulu at the London Stereoscopic & Photographic Company. The portraits are incredibly stiff: ours shows a shy and uncomfortable-looking Kalulu holding a gun behind a serious Stanley. Another in the series shows Kalulu serving tea to a severe-looking Stanley who has a riding crop conspicuously propped on his knee. As a sign of the times, neither of these two photos even acknowledges Kalulu in the captions. However, a third pictures Kalulu alone, in dungarees, boots, and with his khanga (sarong) wrapped around his shoulders and an incongruous fan in his hands. The first two photos clearly situate Kalulu in a subservient role—behind Stanley and with his eyes cast downward and aside. And yet the third photo (even with its offensive caption that implies Kalulu is somehow owned by Stanley), mentions Kalulu by name and presents a self-possessed boy.

What do these photos tell us? It's hard to say, but there is some information about Kalulu's travels with Stanley. From 1872 to 1873, Kalulu accompanied Stanley around Europe and America and during that time sat for a wax model (along with Stanley), which was installed at Madame Tussaud’s museum; he was presented to Emperor Napoleon; ate at banquets in fancy Western dress; and walked alongside Livingstone’s casket in his London funeral. Kalulu was also enrolled in a school in England by Stanley, where the headmaster reported Kalulu was “clever” and progressing in English. However, after Livingstone’s death in 1874, Stanley decided to pick up where the missionary had left off, and took Kalulu back with him to Zanzibar to take what would end up being a 7,000 mile journey across the continent into the Congo to find the source of the Nile. On this trip in 1877, Kalulu died in a tragic canoe accident on some falls that Stanley later named in his honor.

What we are left with is a complicated history between Stanley and Kalulu. Stanley sets up a clear power dynamic between himself (a self-interested white man not afraid to use the media to aid fame and fortune) and a young African boy in our photo. On the other hand, Stanley’s writings suggest the endearing attitude he had toward Kalulu and many of the men to whom he owed his survival and success in Africa, and he seems to have some understanding of the problem of being a “self-invited” guest in the country. On the one hand, Stanley wrote a children’s book based on Kalulu's life dedicated to the end of slavery in Africa. On the other hand, he helped King Leopold II of Belgium create the Congo Free State, which led to horrific mass killings and abuse of Congolese people. Stanley was ashamed to present his drunken half-brother and cousin to Kalulu in Europe, and yet used some racist language and condescending terminology to refer to his friend and loyal companion. Stanley expressed a complicated mix of paternalism, indifference, and love towards both Africa and Kalulu.

One thing is for sure: we cannot know Kalulu’s story in his own words. And so, while our photo does leave us with many questions, in another sense, it does give a clear picture of how history contains very few clear cut answers.

Produced by the Smithsonian Institution Archives. For copyright questions, please see the Terms of Use.

Leave a Comment