This post is the third in a series this month that honor the anniversary of the famous Scopes Trial held in Tennessee from July 10–21, 1925. We're highlighting a set of rare and newly digitized photographs from the Smithsonian Institution Archives collections, of witnesses at the trial, which have been added to the Smithsonian Flickr Commons.

On Wednesday afternoon, July 15, 1925, after two Rhea County High School students were grilled in court about what John Thomas Scopes had (or had not) taught them about evolution, the prosecution rested. Attorney Clarence Darrow began the case for the defense.

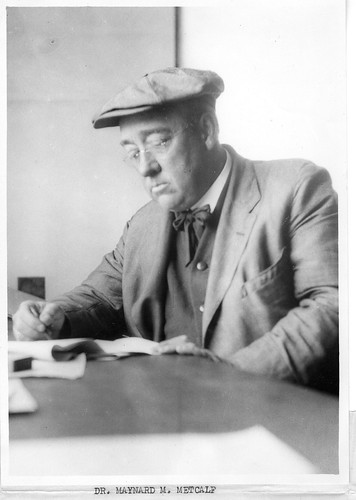

His first witness, middle-aged invertebrate zoologist Maynard Mayo Metcalf (1868-1940), took the stand. Metcalf explained that, in addition to his extensive scientific credentials and publications, he was an active member of the Congregationalist church, and had taught a Bible class for about three years. The scientist responded to Darrow's questioning for under an hour, carefully and conscientiously distinguishing "between the facts of evolution and the numerous theories of how evolution came about." He was a good choice for opening witness—measured, calm, and precise.

A native of Ohio, Metcalf had earned graduate degrees from Johns Hopkins University and Oberlin College, and had been teaching for several years in the Oberlin zoology department. In 1925, he was chairman of the National Research Council's division of biology and agriculture and about to become a professor at Johns Hopkins. That spring, he also received an honorary research appointment at the Smithsonian Institution.

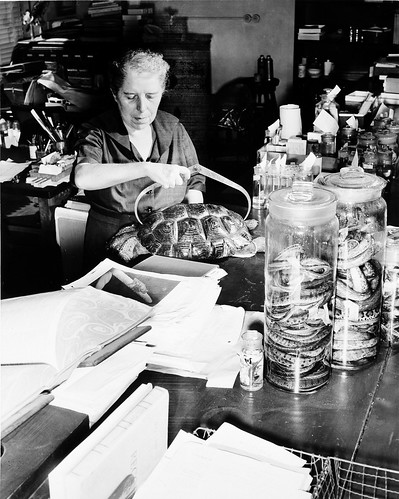

Metcalf's connection to the Smithsonian had begun around 1915, when he corresponded with Leonard Stejneger, senior biology curator at the US National Museum (today’s National Museum of Natural History). Metcalf’s research involved examining intestinal commensal parasites (Opalinidae) in preserved specimens, such as found in the Smithsonian collections, as a way to study the geographical distribution and evolution of frogs. In summer 1924, about to transition from Oberlin to Johns Hopkins, Metcalf asked if he might have a desk in the museum to work on the collections. Metcalf also signaled his intention to donate hundreds of specimens obtained from India and the Philippines. In March 1925, Charles Doolittle Walcott, Secretary of the Smithsonian, offered Metcalf an honorary appointment as a collaborator in the Division of Marine Invertebrates. As curator Waldo LaSalle Schmidt explained, Metcalf was not only doing good work but might also obtain specimens for the museum during a forthcoming research trip to Brazil.

When discussing their work with colleagues, scientists often reveal a sense of play. Metcalf, for example, frequently described the "fun" he was having whenever research investigations opened "along unforeseen lines." He also acknowledged that good science required diligence and patience. "It is hard to put anything new across, and is especially hard in a field involving such...controverted hypotheses as those postulating former land connections," he wrote to Smithsonian Secretary Charles Greeley Abbot in May 1934.

In his scientific correspondence, Metcalf also mentioned an unexpected obsession, one that might seem at odds with his scientific productivity and his pensive, almost melancholic face and yet which, upon reflection, requires traits similar to those found in the best researchers.

In 1920, Metcalf explained to Stejneger that one paper would be "about ready to send you now, but when I first reached home I found my appetite for work below par and so gave a month to laziness and golf" (November 17, 1920). A few months later, he wrote that when that same manuscript "is finally off my hands I hope to celebrate by a couple weeks of golf, the pleasantest form of dissipation I know" (February 15, 1921).

Metcalf also worked with Smithsonian herpetologist Doris Mable Cochran. Years later, Cochran described Metcalf as "a large, quiet man with mild, bluish eyes and a gentle voice," who already "ran to girth" when she first met him in the 1920s. And, she added, he "was very fond of golf," and "sometimes came to my office in the thick hose and baggy knee-length trousers that were then the style on the greens." (undated notes in Record Unit 7151, Box 7, Folder 17)

Metcalf's calmness and precision were of little avail in the Scopes trial, where hot tempers and antediluvian ideologies raged. Such traits, however, probably served him well on the tees and greens, where the contests between player and course defy ideology and offer "the pleasantest form of dissipation."

Produced by the Smithsonian Institution Archives. For copyright questions, please see the Terms of Use.

Leave a Comment