From the beginning, photography upset conventional ideas about the relationship between life and art by altering the way we perceive reality. Ralph Waldo Emerson had some very definite ideas about this: describing his first camera portrait in October 1841 (only a year after photography had arrived in this country) he wrote in his journal: “Were you every daguerreotyped, O immortal man? And did you look with all vigor at the lens of the camera . . . to give the picture the full benefit of your expanded and flashing eye?” Emerson further characterized his portrait sitting as a play between the inner man and his outward countenance. In an effort to have his portrait present the serious face of an important American writer, he writes that he clenched his fist as if “for flight or despair” and muscled his brow into a fearsome frown, and made his eyes “fixed as they are fixed in a fit, in madness, or in death.” And while most of us are often unhappy with the results of the camera’s work, Emerson finishes with a thought that really strikes home: when the image is finished, while “the hands are true,” and the shape of the face is clear and correct, unhappily, the expression of the sitter is that of a “mask.” The fault as Emerson saw it was not whether or not the photograph did or did not capture our likeness, but that it fixed us at that moment for all time. Rendering the ephemeral as permanent implied the possibility of images that might themselves exert greater influence on viewers than the actual subjects. The photographer hero of Emerson’s friend, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s novel The House of the Seven Gables declares that “While we give [the image] credit only for depicting the merest surface, it actually brings out the secret character with a truth that no painter would ever venture upon . . .” Like the stories of Edgar Allen Poe, (who also wrote about the nature of photography) the photographic image raises the issue of the supernatural by virtue of the perfection of its description of things pictured out of the ordinary, “a place where the Actual and the Imaginary meet.”

From the beginning, photography upset conventional ideas about the relationship between life and art by altering the way we perceive reality. Ralph Waldo Emerson had some very definite ideas about this: describing his first camera portrait in October 1841 (only a year after photography had arrived in this country) he wrote in his journal: “Were you every daguerreotyped, O immortal man? And did you look with all vigor at the lens of the camera . . . to give the picture the full benefit of your expanded and flashing eye?” Emerson further characterized his portrait sitting as a play between the inner man and his outward countenance. In an effort to have his portrait present the serious face of an important American writer, he writes that he clenched his fist as if “for flight or despair” and muscled his brow into a fearsome frown, and made his eyes “fixed as they are fixed in a fit, in madness, or in death.” And while most of us are often unhappy with the results of the camera’s work, Emerson finishes with a thought that really strikes home: when the image is finished, while “the hands are true,” and the shape of the face is clear and correct, unhappily, the expression of the sitter is that of a “mask.” The fault as Emerson saw it was not whether or not the photograph did or did not capture our likeness, but that it fixed us at that moment for all time. Rendering the ephemeral as permanent implied the possibility of images that might themselves exert greater influence on viewers than the actual subjects. The photographer hero of Emerson’s friend, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s novel The House of the Seven Gables declares that “While we give [the image] credit only for depicting the merest surface, it actually brings out the secret character with a truth that no painter would ever venture upon . . .” Like the stories of Edgar Allen Poe, (who also wrote about the nature of photography) the photographic image raises the issue of the supernatural by virtue of the perfection of its description of things pictured out of the ordinary, “a place where the Actual and the Imaginary meet.”

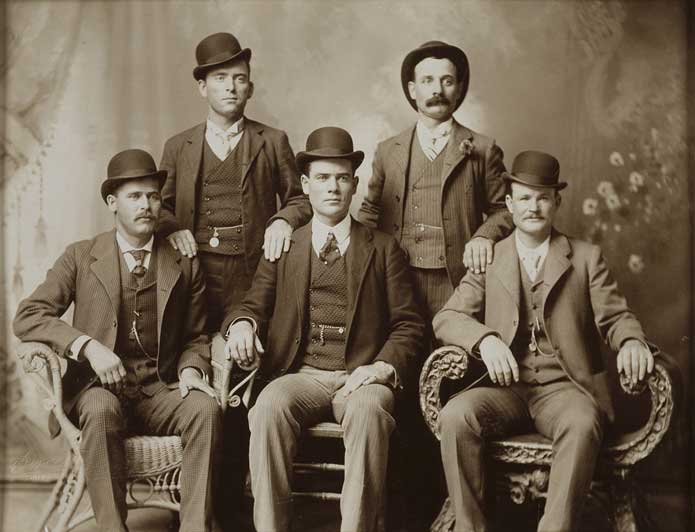

What do historical archives tell us about our current selves? The vast photographic collections of the Smithsonian’s National Anthropological Archives hold images created and used by a range of scientists and explorers that have become the evidence of the early years of what has now become the sub discipline of visual anthropology. Ethnologists, geologists, geographers, soldiers, and merchants all needed images to understand, describe, or organize the colonized countries. By and large, it was an interpretation made by white men for white men. But while addressing these historical materials we might also consider, as visual anthropologist Elizabeth Edwards pointed out in her click! photography changes everything piece the meaning and authority of photographs change, depending on how they are used and who they are seen by. The collections of the National Portrait Gallery show us the faces of great and or notorious Americans. The iconic face of terror that Bruce Hoffman describes in his essay for click! is a further reminder that images demand a context and a purpose. Who would guess that John Swartz’s photograph of dapper gents in bowler hats were otherwise known as Butch Cassidy and the Wild Bunch?

What do historical archives tell us about our current selves? The vast photographic collections of the Smithsonian’s National Anthropological Archives hold images created and used by a range of scientists and explorers that have become the evidence of the early years of what has now become the sub discipline of visual anthropology. Ethnologists, geologists, geographers, soldiers, and merchants all needed images to understand, describe, or organize the colonized countries. By and large, it was an interpretation made by white men for white men. But while addressing these historical materials we might also consider, as visual anthropologist Elizabeth Edwards pointed out in her click! photography changes everything piece the meaning and authority of photographs change, depending on how they are used and who they are seen by. The collections of the National Portrait Gallery show us the faces of great and or notorious Americans. The iconic face of terror that Bruce Hoffman describes in his essay for click! is a further reminder that images demand a context and a purpose. Who would guess that John Swartz’s photograph of dapper gents in bowler hats were otherwise known as Butch Cassidy and the Wild Bunch?

Merry Foresta is the Former Director of the Smithsonian Photography Initiative.

Produced by the Smithsonian Institution Archives. For copyright questions, please see the Terms of Use.

Leave a Comment