This post is the second in a series this month that honors the anniversary of the famous Scopes Trial, held in Tennessee from July 10–21, 1925, and highlights a set of rare and newly digitized photographs, from the Smithsonian Institution Archives, of witnesses at the trial collections, which have been added to the Smithsonian Flickr Commons.

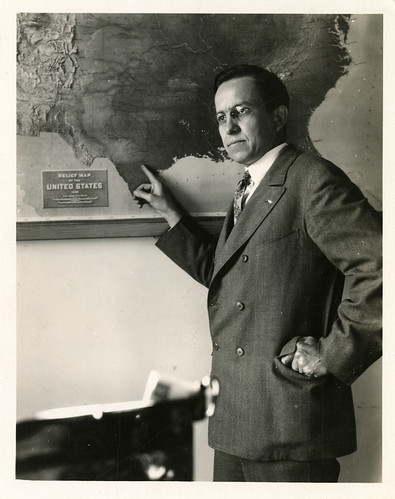

In tone, composition, and setting, the Smithsonian Institution Archives’ portrait photographs of scientific witnesses at the Scopes trial typify the kind of images the syndicated science news service, Science Service, gathered for its files. Some are formal studio portraits, supplied to the news organization by employers. Others show scientists posed in their laboratories or offices, with symbolic props like books, maps, and microscopes. A third group comprises snapshots of people or events, usually taken by Watson Davis or another staff member.

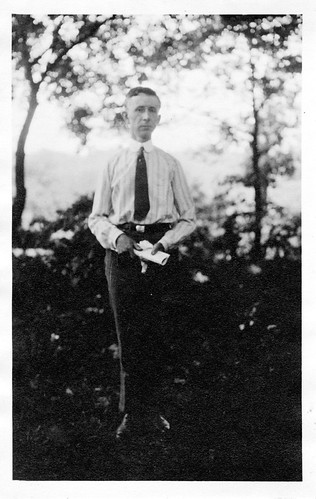

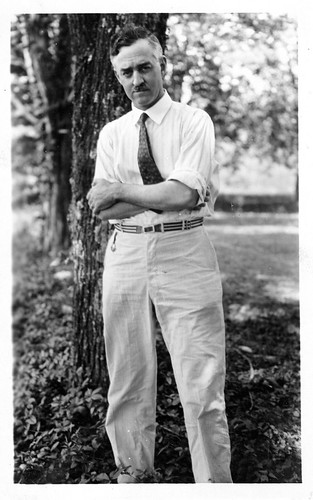

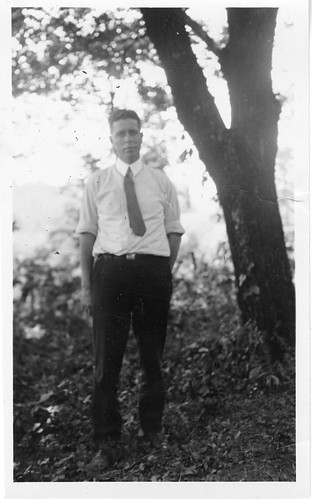

But because Davis and fellow journalist Frank Thone boarded at the defense team’s lodgings, dubbed "Defense Mansion," they could also easily snap less formal photographs of the visiting experts. Thone, for example, posed his subjects in front of nearby woods. With arms crossed or sleeves rolled up, the men look defiant and eager for the evolutionary battle.

The University of Chicago (Thone's alma mater) was well-represented at Dayton. Charles Hubbard Judd (1873-1946), head of the university's department of education since 1909 and its department of psychology since 1920, had become known for applying experimental psychology to classroom instruction techniques.

Alabama native Horatio Hackett Newman (1875-1957) received his PhD from the University of Chicago in 1905 and had been a professor of zoology there since 1917. Newman, too, engaged in cross-disciplinary analysis, later collaborating in psychological and genetic studies of identical and fraternal twins.

The third Chicago faculty member was anthropologist Fay-Cooper Cole (1881-1961). Camping at Defense Mansion during the summertime probably seemed easy for Cole since he had conducted ethnological research in such places as Borneo, Java, and Sumatra. In 1925, he had just been appointed associate professor of anthropology at the University of Chicago, where he later established and chaired the anthropology department.

Perhaps the most accomplished participant was agronomist Jacob Goodale Lipman (1874-1939), dean and director of the New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station at Rutgers University. Despite the demands of extensive administrative responsibilities and research, he had told the defense team that he only needed to know "whether you need me and when."

Winterton Conway Curtis (1875-1969), professor of zoology at the University of Missouri, had earned a PhD from Johns Hopkins University in 1901. Participation in the Scopes trial remained such a point of pride that Curtis included "Expert witness, Scopes trial, Dayton, Tenn., 1925" in his Who's Who biography.

Two experts had connections to the University of Virginia. Biology professor William Allison Kepner (1875-1971) was teaching in the summer session but willingly rearranged his classes to make himself available. Geologist Wilbur Armistead Nelson (1889-1969) was scheduled to join the Virginia faculty and become State Geologist of Virginia on September 1, 1925. Nelson had been State Geologist of Tennessee since 1918, was past president of the Tennessee Academy of Sciences, and was locally known as president of the Monteagle Sunday School Assembly, an interdenominational Chautauqua and summer resort established in the 1880s on the Cumberland Plateau above Dayton.

William Marion Goldsmith (1888-1955) taught biology at a Methodist institution, Southwestern College, in Kansas. Soon after joining the faculty in 1920, he had begun an attempt to reconcile evolutionary theory with the Bible. His 1924 book Evolution and Christianity resulted in an unsuccessful attempt at academic censure, and shortly thereafter Goldsmith moved to the University of Wichita.

One of the last to arrive was Harvard University geologist Kirtley Fletcher Mather (1888-1978), who possessed a useful combination of scientific credentials, experience, and religious affiliation. Mather had earned a PhD at the University of Chicago and could testify knowledgeably about Tennessee geology because he had conducted research there. In addition, he was active in the Baptist church.

The scientists' willingness to make the arduous journey reflected their commitment to repelling assaults on the teaching of evolution. Curtis' train journey from Missouri to Tennessee, took from noon on one day until 6 p.m. the next. Mather had begun his train trip to Dayton from Nova Scotia, Canada.

None of these men got a chance to stand up for science in the courtroom. On the trial's fifth day, July 16, the judge ruled that testimony from the defense experts "would shed no light" on the issues at hand, although their written statements could be read into the record. Only one scientist had been allowed to testify on the stand. It turns out that he was also the witness with a Smithsonian connection.

Stay tuned for more on the Smithsonian's connection to the Scopes Trial next week in this series’ third, and final, post.

Produced by the Smithsonian Institution Archives. For copyright questions, please see the Terms of Use.

Leave a Comment